UPDATE:

replies here: I have thoughts, so stay tuned…As I wrote in a comment on his post:

At least half of the weird terms are like this—terms that have outgrown their original usages and now have their own meanings in an academic canon that Ari is just not privy to (which is why he would consider taking one of those courses in the first place).

To be fair to Ari, he hasn’t had exposure to the admittedly out-there in-group college course language that would allow him to understand some of these course descriptions. And to be clear, I’m not a fan of academic “theory” terminology—I suspect that the push to make one’s contributions “unique” and make a contribution to the academic canon that feels meaningful causes people to come up with weird terms that frankly do not need to exist1.

But in my opinion, once you get past the initial weird language, many of these courses have interesting things to say and can teach you a lot about the world.

Because of this, I feel the need to speak up in defense of these course descriptions. My hope is to interpret and demystify some of the “woke” language used in these course descriptions, and offer a reasonable and charitable guess as to the actual interesting contents of these courses. And at the end of this post, I’ll give some of my larger thoughts on the purpose—and “utility”—of college.

Here goes!

Quick takes on classes

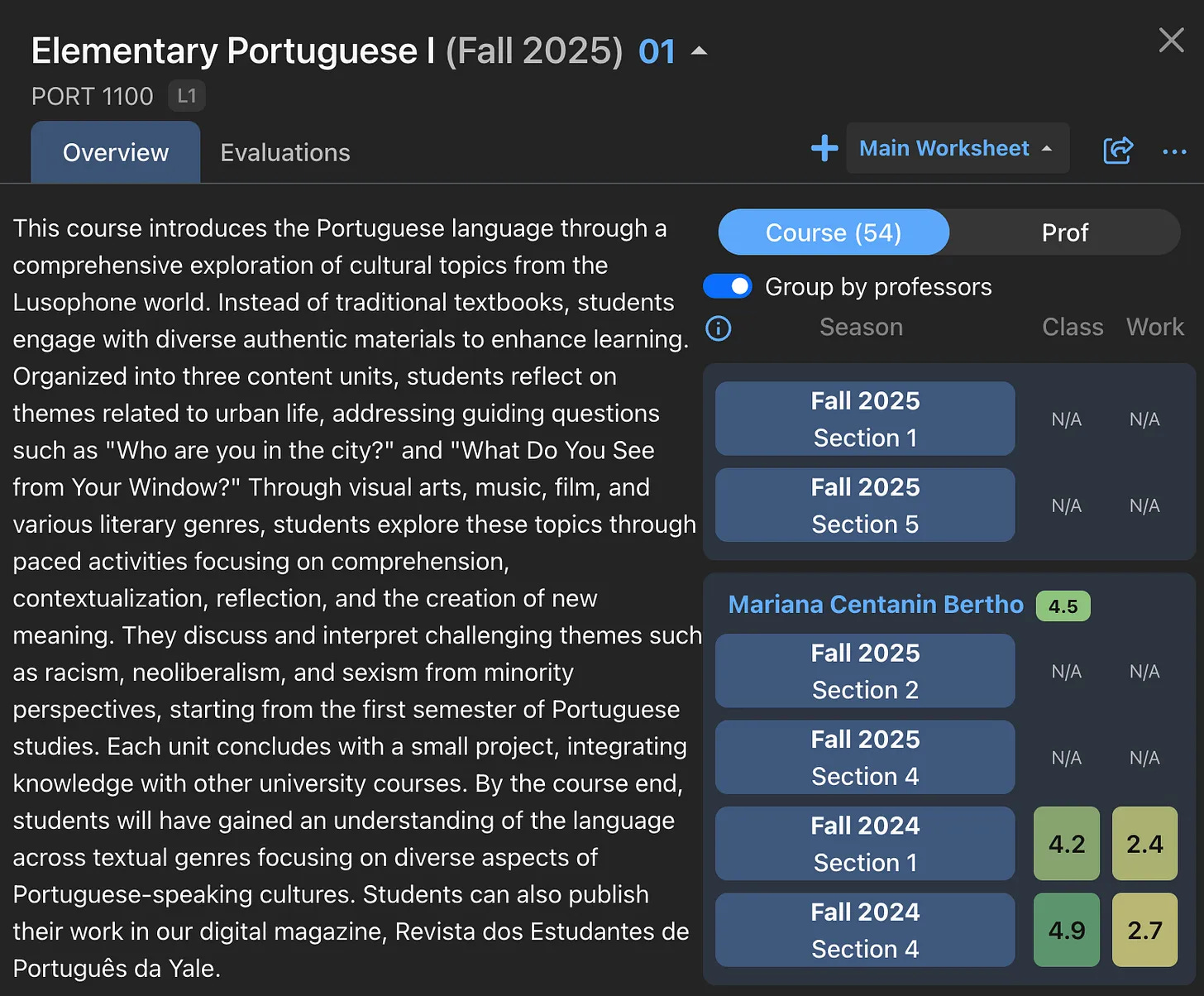

Elementary Portuguese I

Ari says:

Why, pray tell, would an introductory Portuguese class need to interrogate racism, neoliberalism, and sexism?

Well, if someone's looking to become a scholar in Portuguese, perhaps doing some kind of gender or race studies, it would be very important for them to have the language background to engage with texts written in Portuguese. Same with someone who is looking to analyze how neoliberalism has affected Portugal and Portuguese-speakers—I suspect it's being used here as a shoo-in for "colonialism", which Portugal notoriously did a lot of.

I’m also really curious about the mention of “Portuguese-speaking cultures”. Like many other colonial countries2, Portugal no longer has a monopoly on its own language. In fact, Brazil has 20x more Portuguese-speakers than Portugal itself! Thus, any reasonable Portuguese 101 class would have to be culturally diverse and account for colonialism. This seems fine to me.

Social Theory of the City

Readings draw from theoretical formations including but not limited to urban ecology, political economy, political ecology, neoliberal urbanism, critical race studies, critical Indigenous studies and settler colonial studies, feminism, queer theory, and more. A primary aim is to trouble the spatial, temporal, and conceptual bounds of what qualifies as the "urban," and to consider how distinct ways of imagining the city can and do support a range of political agendas and social movements.

I think this course description truly just makes sense. If I took that class, I'd probably be annoyed at the virtue signaling and "woke" language, but I guarantee that I'd probably learn a lot about how the people who first established cities built them around race divisions and on top of the lands of Indigenous people (re: colonization), about things like the drag Ballroom scene of the mid-19th-century.

The Ballroom scene (also known as the Ballroom community, Ballroom culture, or just Ballroom) is an African-American and Latino underground LGBTQ+ subculture. The scene traces its origins to the drag balls of the mid-19th century United States, such as those hosted by William Dorsey Swann, a formerly enslaved Black man in Washington D.C..

What an awesome thing to learn about!

Also, city structure is inherently political3. I live in Chicago and currently intern with the Cook County Office of the Treasurer, so I literally deal with how redlining and property taxes have been used to favor certain parts of the city and worsen Black communities and neighborhoods. The city is genuinely one of the best places for "intersectional" analysis; there are a lot of really interesting perspectives on cities that you’ll never be exposed to on your own!

Histories and Ethnographies of the Corporation

Anthropology 6842—a class for graduate students who want to learn about “early modern corporations and colonialisms; states and corporations; labor; transformations of corporations in the neoliberal era; corporate "culture"; corporate philanthropy; and methodological considerations for conducting research on/in corporations.”

I think that "Histories and Ethnographies of the Corporation" also makes sense! The Corporation as we know it was not always like this, and so of course Anthropologists—the people who study people—would be interested to see how emerging technology and evolving market dynamics changed the initial colonial corporation into the modern corporation, and the culture shifts that came along with it. The shift from mercantilism to capitalism was a monumental development in global history, so of course it would have massive impacts on the corporation. I’d love to take this course!

Hemispheric Poetics & Politics

This is a Spanish comparative literature class that covers:

the so-called Banana Wars, the disintegration of the Good Neighbor era, the inter-American Cold War [what?], US-backed dictatorships and occupations, the neoliberal national security complex, and how these foreign policies "come home." Writing in real time or decades later, we consider how poets "sing," witness, document, confront, or denaturalize [🙄] these hemispheric realities, write in tension or collaboration with others across borders, and create transformative knowledges that allows us to see—and read—the American hemisphere differently.

The inter-American Cold War is literally just a term that describes how the Cold War’s effects on the fate of North and South America was mostly fought by countries in the Americas themselves.

Tanya Harmer argues that this battle was part of a dynamic inter-American Cold War struggle to determine Latin America's future, shaped more by the contest between Cuba, Chile, the United States, and Brazil than by a conflict between Moscow and Washington.

The term is literally just meant to shake off the perception of the “Cold War” dynamic as a battle between Washington and Moscow—because to the people in Latin America, the Cold War was less about Russia and more about how the United States kept messing with their governance and political economy.

Also, the Banana Wars are the chief example of US interventionism in Latin America, in which we literally sent the marines to defend our stupid fruit companies. We are responsible for many of the stupid and evil regime changes and country-wide destabilization in the region, so of course we'd want to see the resulting stories and culture shifts that we caused. I'm not sure why the course so heavily emphasizes poetry, but I’d personally be willing to give the professor the benefit of the doubt—they probably know something that I don’t. I would love to take this course!

Special Topics in Performance Studies

We explore how different ideas of virtuosity, risk, precarity, radicalism, community, and solidarity are shaped by space and place. We reflect on the ways in which performance has been unevenly recorded and disseminated to remap histories of the field. We rethink how local dance and theater economies are governed by world markets and neoliberal funding models and ask how individual bodies can intervene in these global systems.

Ari says:

For years, theater majors have asked, Why won’t anyone buy tickets to my local community theater production? Finally, this course answers: Neoliberalism, of course!

I mean, yes. People won't buy tickets to local community theater productions because we have streaming services and movie theaters. Of course someone has to study this. And of course, if you’re studying to be a performer of some kind, you’d ideally have some understanding of how market dynamics have evolved to eliminate some forms of performance art from existence (or at least existence as a profitable way to sustain oneself). This is inextricably tied to capitalism and market dynamics, which neoliberalism is probably just a shoo-in for. I wouldn’t take this course myself, because I’m not a performer and I don’t do performance studies, but I’m sure it would be interesting for someone who participated in either.

Lastly, we have:

Bodies and Pleasures, Sex and Genders

We will consider how terms like "women" and "men," "femininity" and "masculinity," "homosexuality" and "heterosexuality," and "gender" and "transgender" have structured people’s experiences and perceptions of bodies – their own and others’. We will interrogate the dynamic and often contested relationship between "gender" and sexuality," and their constitution through other axes of power and difference, including race, class, and (dis)ability.

Ari says that this is

The coup de grâce, as far as I’m concerned

But in my opinion, even more than anything else Ari has listed, this one just seems correct. If you've never realized that femininity and masculinity affect the way that people perceive their bodies, or that conceptions of what are traditionally feminine or masculine are highly affected by race (picture a tradwife and trad-husband in your head. Now tell me what they look like and what race they are), or that feminine or masculine high fashion are EXPENSIVE and thus wearing certain feminine or masculine clothing like fancy dresses or expensive suits are class-based (and accordingly your perception of yourself as a masculine or feminine person), I don't know what to tell you. This also seems like a course I’d love to take!

So what is the point of these courses? (and college as a whole?)

I think Ari is being a little unfair when he says that the course descriptions are completely deranged. Incomprehensible I'll give to him, but I think that the actual content is way more grounded than he might suspect. Now obviously not all courses like this are going to be great, and some courses actually will be as “woke” or performatively leftist as one might expect, but some of them truly might change the way that you look at the world.

I'm not going to defend the rest of the courses individually, but I would urge prospective college students (and potentially judgmental readers) to exercise caution before deciding that the content of these courses is actually actively deranged. As Ari himself points out, it's often “the language used to describe them” that throws people off. If you can get past the woke virtue signaling4 you might learn a lot of new things, such as how 19th and early 20th-century Marxist and anti-colonial theory is actually probably pretty relevant to the climate crisis.

But my final point is not about any specific course. In his post, Ari also writes that

The point of the university is to train people to work useful jobs, and think clearly, and do good things, right?

And to be honest, I simply disagree. To me, the point of the university is to learn and produce knowledge.

Look. I understand the overarching criticism, and on some level agree with it. College courses, especially in the humanities, can feel the need to be “everything-bagel” about the knowledge that they impart on students and the political lens through which they teach. There’s an unspoken (and sometimes actually spoken) pressure to be “woke” about the injustices that we face, especially regarding particular topics like neoliberalism. And some knowledge is simply going to be more timeless or useful than others.

But to be fair to those courses, we’ve been living in the capitalist mode of production for many, many years now. Of course every facet of our culture and lives has been affected! Many of these effects are really interesting and have fascinating historical origins that have been uncovered by the professors of ages past—and if you’re interested, you can learn about them from the professors of today!

I’m not saying that you have to learn about these things, or approach college from this kind of lens. There’s nothing wrong with what Ari says he’s planning to do, which is to register for lots of math classes, and a few humanities sections with normal descriptions.

I’m just giving a warning: that’s what I did, and I regret it!

There have been so many times over the past few years where I've had wonderful discussions with people taking courses I never would have registered for on my own, like native perspectives on the Banana Wars or gender abolition through the perspective of gender studies or the new proposed geological era of the Anthropocene and the sensing of it through the construction of the modern city. There are so many other “woke” things I’ve learned almost against my will and been super fascinated by, like DuBois’ Double Consciousness and also literally Karl Marx’s own theories of history and economy5.

So, if you’re going into college, I’m begging you: please do it with an open mind. There’s so much to learn here—and all you have to do is assume that your peers and professors are just as smart and clear-headed as you are. This is a once in a lifetime opportunity for you.

And, hey. If, at the end, you come out radicalized against the woke liberal leftists, that’s totally fine. I’m not asking you to believe what I believe; I’m just asking you to give it a fair shot.

I left a comment on Ari’s post that sums up my case pretty succinctly:

When I was a math TA for our intro-level calculus courses, I ended up teaching a bunch of humanities people the rigorous delta-epsilon definition of limits, along with the Riemann sum trapezoidal integration necessary to define an integral. I'm a physics major, and even I never really used either of those things beyond my intro calc classes—most people don't need to know how to do an integral beyond their college years (and also you should really just google how to change a lightbulb).

Even though I was a physics major, I was "forced" to study Descartes and Hume in my philosophy classes, and Locke and Hobbes and Smith and Marx in my social and political theory classes. I'm really glad I did, because I no longer study physics—I work for my local county government in Illinois, where political philosophy is suddenly a really important thing for me to understand—and if I hadn't had such a comprehensive education on things I found "useless" at the time, I would be worse off for it.

But "useless" is still missing the point. I think that Universities are places for knowledge learning and production. They aren't always seen this way, because college degrees have become signaling mechanisms and are seen as standard for all employment (but that's a separate topic). The point I'm making is just that "efficiency" or "utility" is not what most of the top-tier colleges are designed for. The point of a liberal arts education is to provide a foundational understanding of the humanities and social sciences and natural sciences. And Yale is a liberal arts college—so this is exactly what you signed up for (and it's awesome!)

I guess I'm just saying, try to appreciate it for what it is instead of wishing it were something else. Many of your criticisms of college are super valid, but many of them stem from a misunderstanding of college's intended purpose. College isn't solely meant to maximize one's future profits (though it can certainly be used that way by business majors or MBAs but I digress)—it's supposed to be a place of learning, literally for higher education. That's the goal. If that higher education is weird or esoteric, so be it!

There’s an interesting connection here with the Rationalists, who have so many thousands of concepts that their main website—Lesswrong—has a “Concepts” page, but I digress.

*koff* FRANCE *koff*

listen I know that “___ is inherently political” is the most leftist buzz-phrase ever but I genuinely think it applies here so forgive me for using such a cliche

which to be clear is very annoying and can sometimes make class discussions a real pain in the ass

I at some point will write about why I was briefly a Marxist and why I am no longer a Marxist, but for now I will say that reading Capital literally changed how I saw the world and still influences me to this day.

I commented something else on the original post, but I’ll say a word here about all those quotation marks since you didn’t. The point isn’t to be sassy and snide; it is literally to indicate that, say, “homosexuality” is being dealt with initially as a semantic label rather than with the assumption that there is something called homosexuality and that we all know what it is and that the word has always been used in the same way. Is homosexuality a behavior? A lifestyle? An “orientation”? (What does that mean?) Are homosexual desires “perverse,” which implies that only a few people experience them and that they are bad, or are they “base,” which implies that everyone experiences them but that the point is not to act on them? And what constitutes a homosexual desire? Does only an active, articulated desire to have sex with someone of the same sex qualify? The relationship between Ishmael and Queequeg in “Moby Dick” is different from that between Maurice and Scudder in “Maurice,” and not just because the first is more subtextual. Is only the second homosexual, or are both? If we say only the second, then does that make Maurice’s unconsummated relationship with Clive not homosexual?

I haven’t read that much queer theory. I’ve read some that I think is actively bad and unconvincing. (Though even that I ultimately found valuable: https://www.upress.umn.edu/9780816665112/henry-james-and-the-queerness-of-style/.) But it doesn’t take that much exploration to see that categories we think of as received and stable are often not that way, and that a lot can be learned by beginning with treating them as semantic labels rather than as though one already knows exactly what they mean. One of the main things I learned from my course on the “New Negro Renaissance” was that the term “New Negro” was almost entirely a floating signifier, used between 1895 and around 1935 to refer to all sorts of black people and visions of the black future, reflecting a discourse that was highly variegated but united by a progressive impulse such that it was useful for everyone from WEB Du Bois to Marcus Garvey to Jean Toomer to be described as a “New Negro” by somebody.

Some of these defenses are taking charity to the professors a little too far.

For example, the Portuguese course is *Elementary* Portuguese. It would not surprise me if there are dialectal differences between, say, Afro-Brazilians and Euro-Brazilians (legacy of slavery, probably some African language substrate, blah blah). These might be worth studying in an advanced literature or linguistic course. But elementary level in any language is conversations and conjugations, not Theory. You wouldn’t teach ESL via lengthy analysis of how French vocabulary supplanted Anglo-Saxon vocabulary in the wake of the Norman Conquest. Shoehorning in the standard woke shibboleths into the syllabus for an elementary course suggests that the professor prefers droning on about those shibboleths (possibly in English!) rather than, you know, teaching people how to speak and read Portuguese.

Or take the Performance Studies course. I *strongly* doubt that it’s some practical guide to navigating funding for a community theatre. A course like that would probably be cross-listed with the MBA program and include a lot more words like “budget,” “marketing,” and “CRM,” and a lot fewer words like “neoliberalism” and “precarity.”