Order and Chaos

A guest post

Introducing a guest post series! I reached out to authors who have mentioned a topic that I wanted to hear more about, one that’s not necessarily their typical content. These posts are often on questions of metaphysics, philosophy, religion, and their intersection with materialist frameworks, including sciences like physics or biology.

Harjas Sandhu writes on Substack here, and works in policy for Cook County, containing the great city of Chicago! I highly recommend his content on philosophy, psychology, politics and policy, self-improvement, writing, and culture.

I want to give a huge shoutout to Farrah for helping with revising, editing, and fact-checking the neuroscience sections of this post.

emergence occurs when a complex entity has properties or behaviors that its parts do not have on their own, and emerge only when they interact in a wider whole.

I would take this one step further: in my eyes, a truly emergent phenomenon is a property of a complex system that is separate from its constituent parts, insofar as knowing about the behavior of the parts individually is not sufficient to understand the system as a whole. Accordingly, understanding a particular emergent phenomenon does not require understanding its constituent parts.

Take, for example, the job of a dog trainer. A dog trainer has, in some sense, a relatively straightforward job: to make a dog behave. In order to do their job, the dog trainer must have a strong understanding of best practices in the field, and probably also dog behavioral psychology. These best practices are observational; they were probably developed over time by past generations of dog trainers and animal behavioral psychologists, who performed experiments on dogs and recorded the outputs in a relatively scientific way.

However the structures that underlie dog behavior are vastly complex and multilayered. Dogs do not behave the way they do for no reason: they have brains1, and their behavioral psychology is thus entirely mediated by dog neuroscience. But understanding dog behavior does not require understanding the molecular makeup of individual neurons.

Instead, all you have to understand are the higher-level interactions that appear to govern dog behavior, like "consistent reinforcement helps dogs understand what is expected of them" and "inconsistent reinforcement makes it harder for behaviors to die out because the dog won't understand what's going on" and “dogs bark when they see the Amazon delivery guy”. Despite the fact that dog behavior is entirely mediated by dog neuroscience, a dog trainer does not need any understanding of dog neuroscience to perform their job. All they need is to find consistent inputs and outputs to dog behavior.

Thus, I would say that dog behavior is an emergent phenomenon. While it is technically entirely mediated by dog brains—and thus, dog biology—in practice, understanding dog behavior actually has very little to do with understanding dog biology, and everything to do with experimental observation. If your goal is to understand dog behavior, understanding the mechanics of how dog neurons work is actively a waste of your time; dog behavior is not a predictable result of dog neuronal activity, but an emergent phenomenon that should be studied as a related but separate system.

It seems like the complex but legible system of dog behavior is best understood at a high level of abstraction. And this concept applies to more than just dog behavior: when trying to understand any complex but predictable system, deconstructing your system into its constituent parts is often not necessary—and can sometimes be actively unhelpful.

To illustrate, let's analyze another complex system to see what I'm talking about: the weather.

At a macro level, we can observe highly legible weather phenomena (by legible, I mean “comprehensible as unique and complete occurrences”. For example, someone could say something to me along the lines of "Hey, did you know that a cold front is rolling in on Saturday?" or "A hurricane is moving towards Florida", and I would understand what they mean—because hurricanes and cold fronts are relatively well-defined phenomena.

Now, let's go down one level of abstraction. Suddenly, things become less comprehensible. I can tell you that a cold front is moving in, but if you ask me what's going on inside that cold front, I'm going to shrug and throw my hands up. I can tell you how the sea breeze works, but don't ask me which areas are going to be windy at precisely what times. And I can tell you about general macro-level seasonal weather patterns, but even the most advanced meteorology we have today can only reliably predict the weather a few days out. Just like our dog example, in which we can understand that a dog will bark at the Amazon delivery guy without understanding what neurons are firing or what’s going on inside that dog’s brain2, we can more or less understand macro-level weather patterns without really understanding the forces that generate them.

Let's go down one more level of abstraction. Suddenly, we move from local weather phenomena to even smaller phenomena—and we're back in the realm of relative comprehensibility. We end up with things like the Navier-Stokes equations3 that miraculously describe fluid flow in general. From Wikipedia,

They may be used to model the weather, ocean currents, water flow in a pipe and air flow around a wing. The Navier–Stokes equations, in their full and simplified forms, help with the design of aircraft and cars, the study of blood flow, the design of power stations, the analysis of pollution, and many other problems.

In the dog example, an equivalent might be the field of neurophysics, the field which studies (among other things) the physics that governs the interactions between neurons, or biochemistry as it pertains to the molecules that make up neurons (and other cells). If dog neuroscience was one layer removed from dog behavior, these fields might be considered two layers removed—they generate the emergent phenomena that generates the emergent phenomena that we’re studying.

Going back to the weather example, the Navier-Stokes equations are essential for understanding fluid dynamics—but they only apply to viscous fluid substances. In other words, we still haven't reached the bottom layer of emerging phenomena.

If we dive one level deeper, we end up in the realm of individual particle motion. As we reduce the complexity of the system we're studying, it makes less and less sense to treat those particles as a single contiguous unit that we call a viscous fluid, and more and more sense to brute-force calculate the motion of each of the individual particles. We've now reached the level of Newtownian mechanics, where we treat each particle as a single unit and use Newton's Laws to calculate their motion.

But wait. Particles aren't single units—they're collections of atoms, which are themselves made up of subatomic particles. There's one further layer of abstraction for us to dive into: Quantum Mechanics.

Quantum Mechanics is the strangest thing I've ever studied. Particle states are treated probabilistically and are governed by weird principles like Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle, which states that a particle cannot have a fully defined position and velocity at the same time. In other words, a certain amount of its position and velocity are randomly determined.4

But even more strangely, the fact that randomness is fundamentally baked into the universe can be safely ignored by anyone who doesn't care about it. Newton's Laws aren't probabilistic, and they work just fine. In fact, they work so fine that pre-QM physicists believed that the universe was fundamentally deterministic. When Einstein famously said that "God does not play dice", he was arguing that the nature of Quantum Mechanics is an affront on intuition and all of our natural laws. And despite the fact that the lowest level of physics that we know about is not governed deterministically but randomly, somehow, a summation of randomness eventually turns into deterministic predictability.

In other words, it turns out that determinism itself is an emergent phenomenon.

Isn't that wonderful?

Because basically everything can be decomposed this way, complex systems can be thought of as alternating layers of order and chaos, which give rise to one another in sequence.

When I say chaos, I’m referring to the chaos of chaotic systems, defined as systems that are highly sensitive to initial conditions and thus incredibly hard to predict in the long-term. When I say order, I’m referring to the opposite, which are relatively legible and deterministic systems that are relatively stable across a wide variety of initial conditions and are thus comparatively less random and easier to predict.

Order comes from the fact that chaotic systems eventually become governed by probability distributions as they go up—and eventually, the law of large numbers starts to kick in.

Let’s do some statistics so you can see what I mean.

Take, for example, one dice roll. If I asked you to predict the result of a single dice roll, you’d tell me it was impossible—because it is. Every possible value has the same probability of occurring: 1/6, or 16.67%. In other words, this is a uniform distribution.

All graphics are screenshots from AnyDice, which is a spectacular website.

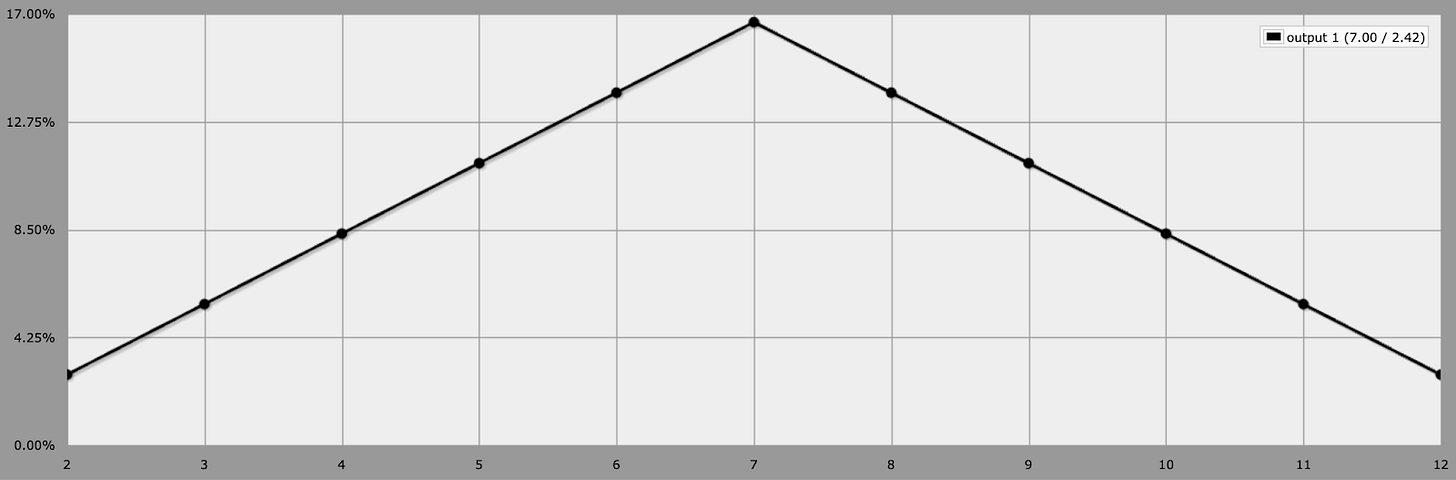

Now, if I asked you to predict the result of two dice rolls added together, there suddenly emerges a correct answer. The odds still aren't that great, but the probability of rolling a 7 is higher than every other number5. By summing together two uniform distributions, we get a probability distribution that looks like this:

What if we roll 3 dice?

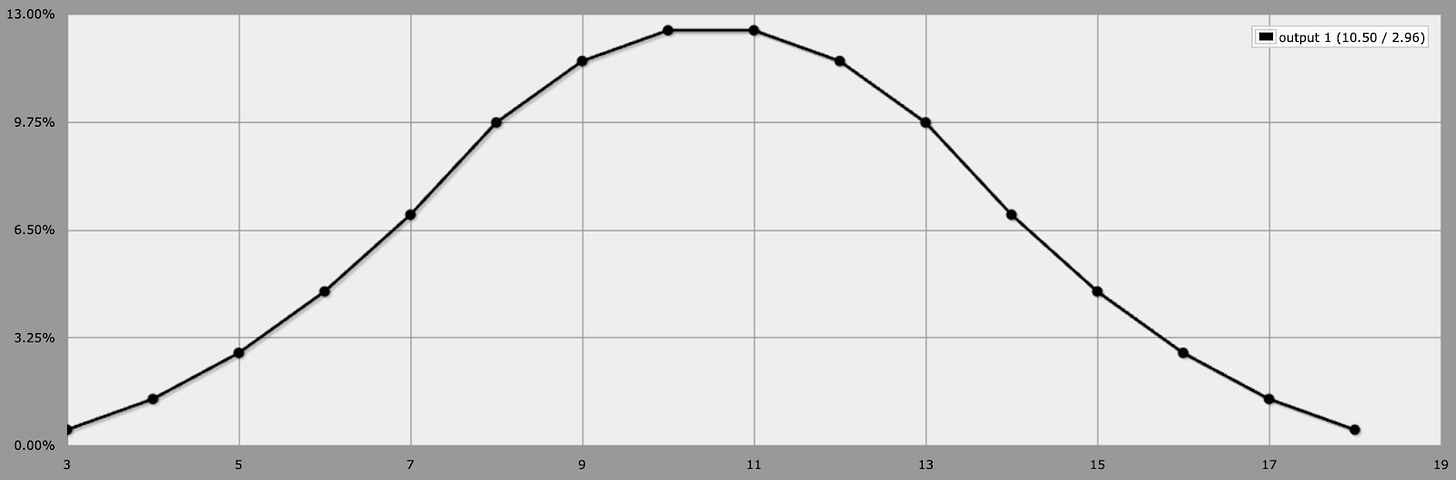

With three dice, something interesting begins to happen. Now that we’ve summed together three uniform distributions, a shape is starting to emerge—the normal distribution (also known as a bell curve or Gaussian distribution). The values around the mean are the most likely to occur, with the mean being the most likely result. The mean is equal to 3.5 x n, where n is the number of dice you roll.

This phenomenon is known as the Central Limit Theorem. It’s most intuitive with uniform distributions, but it actually applies to a wide variety of different distributions:

under appropriate conditions, the distribution of a normalized version of the sample mean converges to a standard normal distribution. This holds even if the original variables themselves are not normally distributed.

In other words, we’re using dice because uniform distributions are nice to look at and easy to understand—but the lesson we’re learning generalizes broadly across events that are governed by probability distributions.

Let’s add some more dice. 10 dice looks like this:

This looks even more like a normal distribution.

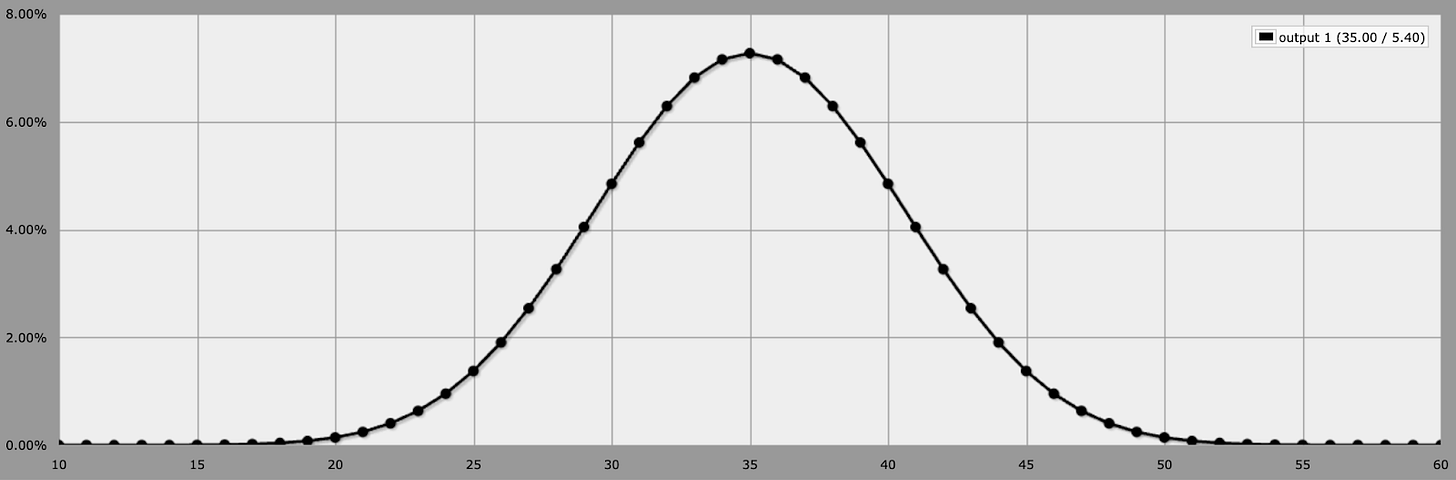

What about 100 dice?

Hang on—something else is happening here. The normal distribution is sharpening, and the range of probable values seems to be tightening; look at those huge swaths of values below 300 and above 400 that are strictly possible but incredibly unlikely.

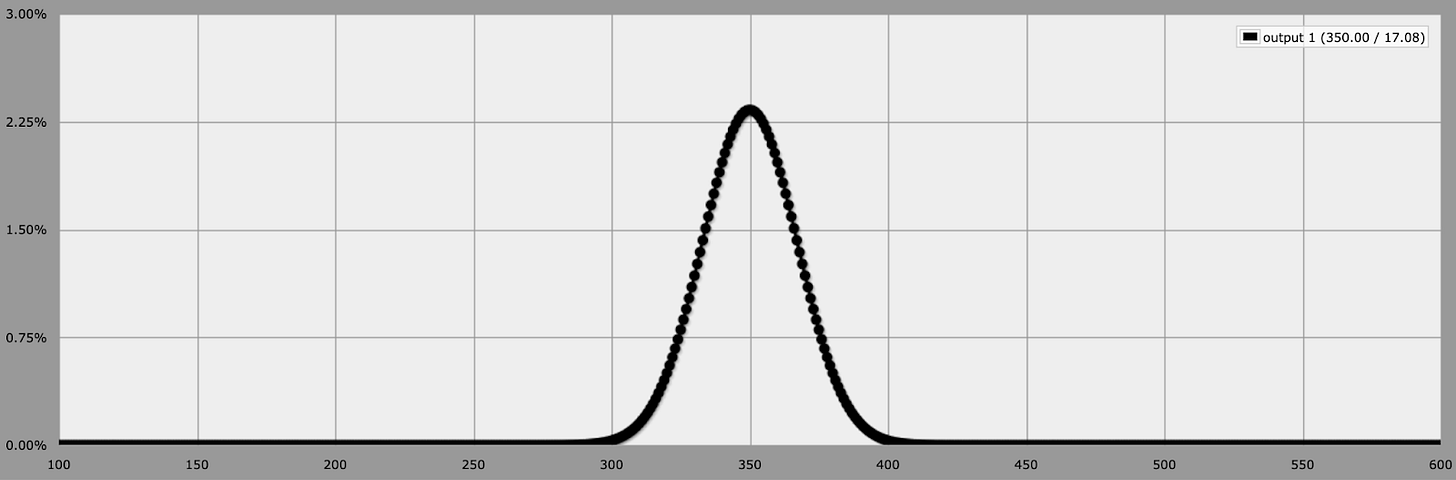

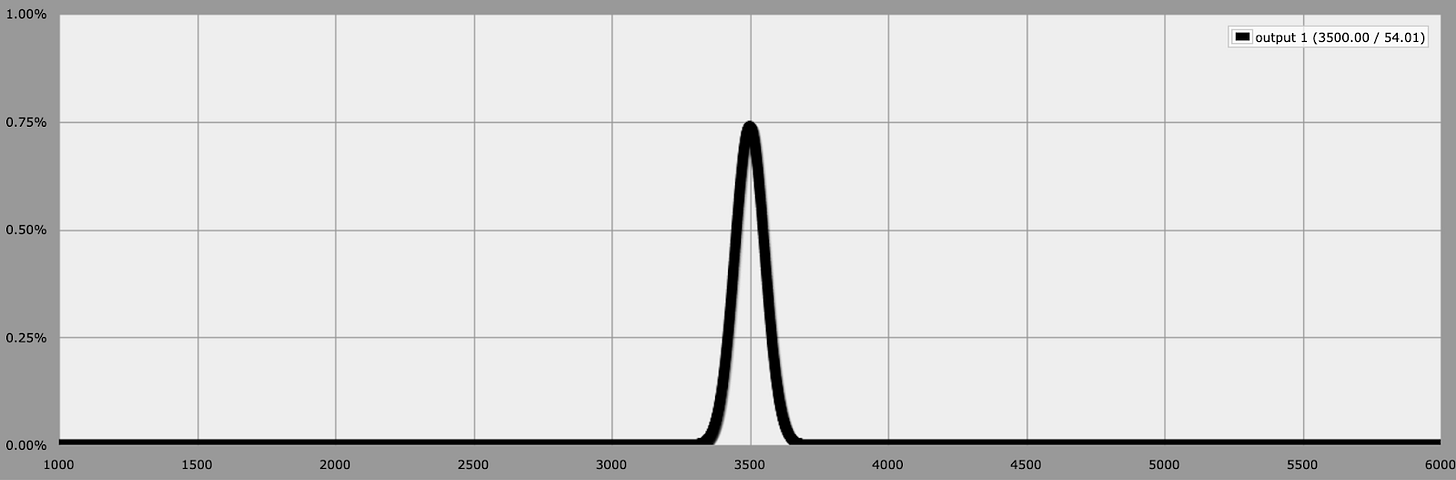

Let’s try one more time, with the maximum amount of dice I can get AnyDice to work with: 1000.

As we can see, something even more interesting is happening now: as we increase the number of dice, the range of possible outcomes tightens even more.6 If I asked you to predict the outcome of 1,000 dice rolls, you could tell me that the answer should be around 3.5 x 1,000 = 3,500 and basically be right—and as the number of dice rolls increases, the calculation only becomes more likely.

To recap: the value of one dice roll is entirely unpredictable, but the sum of a million dice rolls is easy. One dice roll has a uniform distribution and is impossible to predict, but as the number of rolls grows, it becomes normal—and as the number of dice rolls approaches infinity, will eventually become a vertical line.

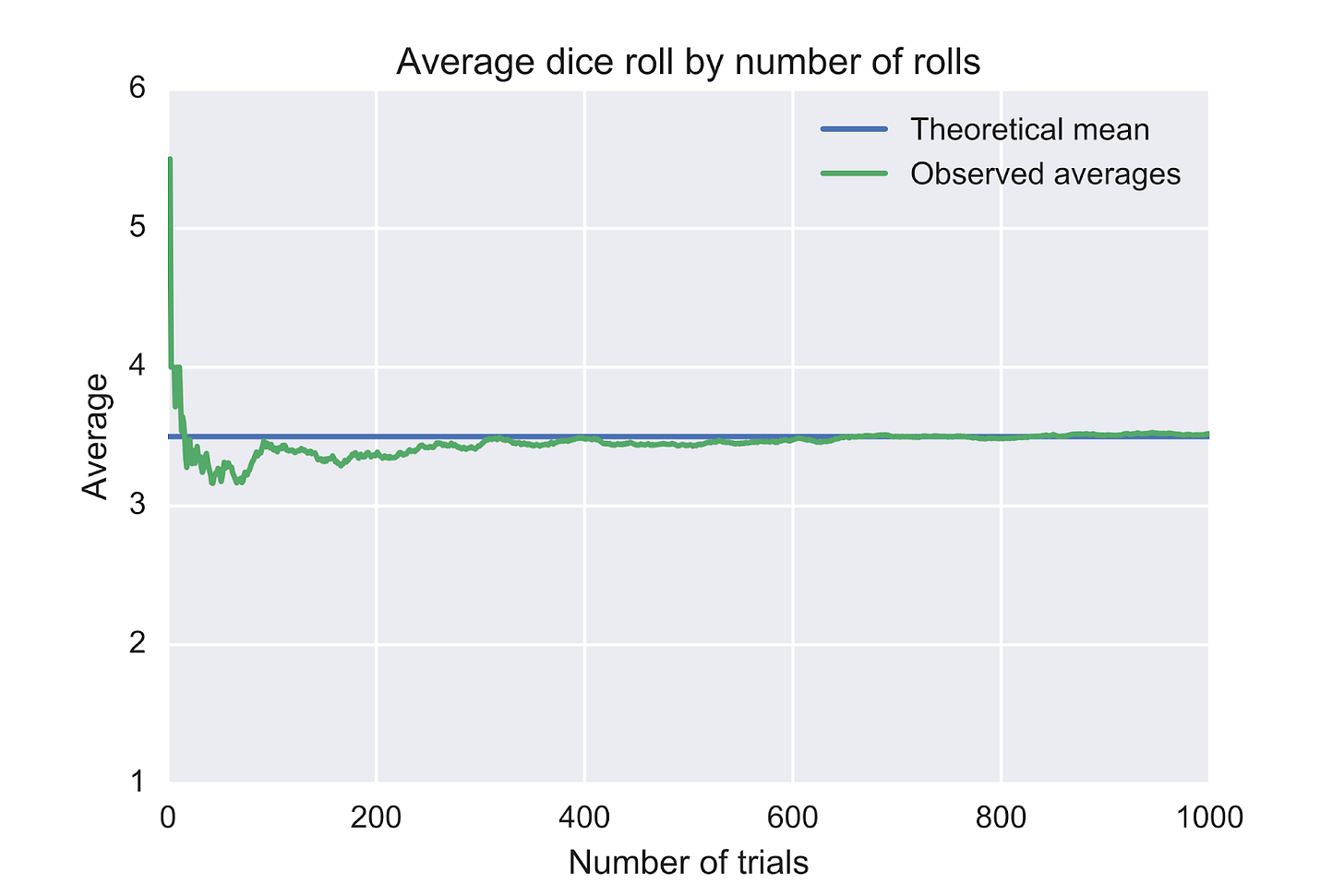

This phenomenon, in which the sample mean converges to the true mean for a sample of independent and identically distributed values,7 is known as the Law of Large Numbers, or the LLN.

the law of large numbers is a mathematical law that states that the average of the results obtained from a large number of independent random samples converges to the true value, if it exists.

In other words, the LLN describes exactly the phenomenon I was talking about. Randomness doesn’t produce order accidentally—at scale, true randomness will eventually produce predictability.

Credit to Pred of Wikipedia.

As long as you take enough samples, your chaos will give rise to some kind of order. All you have to do is zoom out.

So what does this mean practically?

Let’s go back to our complex systems from the beginning. As we discussed, reality comes from semi-discrete layers of order and chaos. Thus, when analyzing these systems—and emergent phenomena in general—we must be very careful to parse out different layers of reality, so as to not generalize hastily.

For example, let’s take the field of economics.

Breaking down every single level of emergence that leads to economics, we have the most ridiculous chain in the world.

Quantum Mechanics (subatomic particles)

Newtownian Mechanics (atoms)

Chemistry (molecules)

Biochemistry (molecules as they give rise to life)

Genetics (applied biochemistry and how genes express themselves)

Microbiology (how genes give rise to cells and cellular biology in general)

Neuroscience (nervous systems as formed by Macro-level Biology)

Physiology (the study of functions and mechanisms in living systems)

Behavioral Psychology (observable behavior of humans that are governed by neuroscience)

Microeconomics (the behavior of individual economic agents)

Macroeconomics (the resulting overall economies at national or global levels)

Each of these levels represents a new level of emergent phenomena. Each of these levels requires its own entire discipline (or sub-discipline) in order to study it properly, because it cannot be properly modeled by the level below it or the level above it. At any given layer of abstraction, layers below and above can provide us with important insights.

For example, let’s say we’re studying behavioral psychology. Neuroscience is highly influential on behavioral psychology, as many of the insights found in behavioral psychology can be further understood by studying their roots in neuroscience, and microeconomics can serve as a proving ground for behavioral psychology through methods such as revealed preferences, which uses individual consumption patterns to track their actual preferences and values (as opposed to traditional survey methods).

Generalizing further: if you’re trying to describe a layer of reality, you may want to also consider learning more about the layers of reality that exist directly above and below in complexity. For simplicity, let’s call these layers A, B, and C, where A => B => C. If you’re trying to learn more about layer B, you should obviously be primarily studying layer B. But studying layer A will sometimes tell you more about the foundations behind layer B, and studying layer C will sometimes tell you about the ultimate consequences of layer B.

And after all this, we finally arrive at the example that prompted me to write this post in the first place. In a recent Noahpinion blog post, Noah talks about the rise of microeconomics and the fall of macroeconomics.

For my first few years as a blogger, I was primarily known as a critic of macroeconomics as a discipline. The data was far too patchy and confounded to warrant most of the strong conclusions that macroeconomists routinely proclaimed. And macroeconomists rarely tested the “microfoundations” (assumptions about consumer and corporate behavior) that undergirded their models. No one ever seemed to be able to draw a definitive conclusion in macro — a lot of it was all just about who could shout the loudest in seminars, or appeal to the right political opinions, or deluge their critics with a blizzard of equations. It was not very scientific.

Microeconomics, on the other hand, seemed a lot like a real science. Micro theory often really worked — auction theory gave us Google’s business model, consumer theory really could predict consumer behavior (and, often, prices), matching theory was used in a bunch of applications, and so on. And on the empirical side, the “credibility revolution” brought causal methods to the fore, allowing us to make good educated guesses about the effects of many policy changes.

This example, particularly the part about “microfoundations”, is a great example of what we've been talking about this whole time. Macroeconomics emerges from microeconomics, but macro really should just be a different discipline. Trying to bridge the gap between the two is a noble endeavor, but macro is a whole other beast that can’t be modeled by micro alone.

On a large scale, economies are driven by more than the simple, rational decisionmaking that underlies microeconomics; macro also has to deal with weird factors like “public trust” and random geopolitical conflicts and weird finance shenanigans like the subprime mortgage crisis that caused the Great Recession in 2008. And while microeconomic theories can sometimes predict future events, many of our macroeconomic tools were discovered through trial and error—for example, the monetary policy of quantitative easing was developed in response to the Great Recession. Country-scale economies might be made up of local markets, but the dynamics that govern local markets cannot be generalized to the larger structures of countries.

More generally, since reality is composed of layers of order and chaos sequentially stacked on top of each other, it makes sense that the order and predictability of microeconomics would give rise to a chaotic system of macroeconomics. It’s possible that at some larger scale, macroeconomics might itself give rise to a new, more orderly kind of economics—maybe if our countries numbered in the thousands instead of the hundreds, so that our central limit theorem could kick in. But even if a new kind of orderly planetary economics emerged from macroeconomics, the laws that governed that new kind economics would probably bear little resemblance to either micro OR macro.8

So, when analyzing a complex system, approach with caution. Be very careful about the bounds of what you know, and be even more careful about the limits of the patterns you discover. There’s no guarantee that laws that initially seem ironclad will continue to generalize past a certain size.

And even more importantly: isn’t this all so cool?

This may be a surprising statement for those of you who have dogs

There’s actually another layer here, which is that individual neurons themselves fire in relatively variable schedules, but still somehow form neuronal ensembles that can be used to generate stable predictions on outputs such as arm movement, but I’m going to gloss over it for the sake of simplicity

I know I was a Physics major but don't ask me to explain this because I won't be able to tell you much about it

In greater detail, Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle states that there are certain coupled properties that can only be measured to a fixed aggregate level of uncertainty, so more precise measurements of one property literally increase the uncertainty of the other set of measurements—for example, precisely measuring the velocity of an electron actively changes its position into a probability cloud that hovers around an atom, not because we don't know where it is but because it no longer occupies a single defined place.

If you’ve ever played Settlers of Catan, you hopefully know this already

For you stats people, it’s true that the standard deviation strictly speaking continues increasing, but the limit of the range of probable values divided by the range of possible values goes to zero.

This has a rigorous mathematical definition that we’re going to gloss over, but if you’re interested I would recommend finding an online textbook or course in probability and statistics

Obviously we’re off in the realm of speculative fiction here—in reality, maybe the order would require even higher scales of thousands of planets, or maybe it’s just chaos after microeconomics, but it’s fun to speculate!